Rypke Sierksma

Contents

1 The Tempo of Shaving

2 Sweat and Tears

3 Walking History

4 Walking In Difference

5 The Metre of Pacing

6 Godspeed

7 Garden Melancholy

8 An Invalid’s Pace

9 Devilspeed

1 The Tempo of Shaving

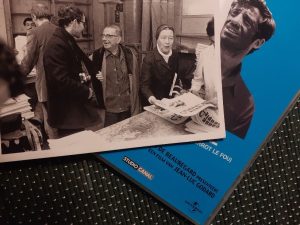

Wim Wenders makes good on the title of his movie Im Lauf der Zeit, in the flow of time. It consists of slow images, calmly feeding one another. Take only its beginning. After the ten minutes which this scene lasts, it feels like one has already been sitting in the cinema for an hour; not so much, because one is bored, but as if time is given to you as a luxurious treat; as if time has been shared out to you.

A roundsman, regularly riding his circuit of a series of cinemas, is delivering metal bins in which, in antediluvian times, reels of celluloid film were stored. His job consists in delivering a new movie to the first cinema in line; picking up the bins with the film this cinema has shown last week; to subsequently deliver these to the next one – and so on. The first shots of Wenders’ movie show us an early morning, with a man calmly shaving himself. He is standing next to the van in which he has spent the night, parked on the bank of a river. As yet, the world is gloriously empty. These first few sounds, the indolent light and his slow, considered movements give certainly the hasty city dweller the impression of time slowed down; time become viscose – time rendered almost timeless

Then, all of a sudden, a lightly humming little sound. An insect? – no, not an insect; rather something enginelike, a sound in a far distance, not yet present in the scene’s here and now. Getting louder, as yet, it’s monotony easily fuses with the tempo of the man’s shaving. While the humming becomes louder, it begins to interfere with the timelessness of his little secluded world. The van-driver is looking up from his shaving-mirror; after some gazing, he perceives a Volkswagen, type Beetle. The little car is driving on a small road further away, coming towards him with a speed that seems to get faster every second, its noise now becoming intolerable. Cinema-viewer and roundsman are expecting this projectile to make a screeching stop; just in time, as the little road ends at a right angle on the stream, point blank at the river bank; once the place for a little ferry-boat, now defunct. However, like a scared cat, the car rockets over the river’s edge, almost toppling over at the impact with the water. Then it comes to a standstill.

A fine example of what I once called John Dewey’s tempi-thesis. For the American philosopher all is an event; nothing is eternal. Decisive are proportion, relationship, ratio and the knowledge of the relative changes in tempo. What we call ‘reality’, merely consists of a range of events, each with its own relative, different tempo. A man’s organism, dependent as it is on its own organically given pace and on the accompanying time perspective, will characterize any event that is slower than itself as more steady, as more rhythmic – as a structure; by contrast, other more volatile and sporadic incidents are experienced as a process. What exceeds man’s own tempo is considered as unstable; often, as unpredictable. What seems eternal from one perspective, ‘Diamonds are forever’, will appear in flux from a different perspective; for instance, in terms of the age of our cosmos. Absolutely everything that is, is in constant decay; panta rhei, even that diamond which supposedly exists ‘forever.’ As Karl Marx phrased it: under pressure, all that is solid melts into air.

In Wenders’ encounter of a chauffeur of a film-van with the approaching VW, two worlds meet; a man, slowly shaving himself as if he has all time in the world; and a crazy racer in a small car who will, after his jump in the river, just be able to save himself. Two extreme tempi of human existence. Yet, it is only from the perspective of the razorblade, calmly skimming and gently feathering the man’s skin, that the racing beetle can become a speed-bomb. This scene is Wenders’ ode to the medium with which he has grown up; the cinema-film, which will later make him world famous; a medium, which is time coagulated in celluloid, depending on the ‘right’ Dolby tempo of the projector and on the darkness of the cinema room, to allow its frozen pictures to, once again, melt into the moving scenes that in turn will move us. A second-hand life.

2 Sweat and Tears

Machiavelli, the advisor of Princes, knew that ‘the world belongs to the one who will keep his head cool.’ In Visconti’s screening of Di Lampedusa’s masterpiece Il Gattopardo, the Leopard, time appears in the garments of the decay of history. At the end of the 19th century Italy, like Germany, experienced her belated birth as a nation-state; up till that moment, it had been made up of a series of small, dispersed princely realms, more or less artificially glued together by la Famiglia and a Machiavellian politics. Compared with other European nation-states, this was a late occurrence; what a biologist would call a Spätgeburt; in the way, that the human infant is suffering its Frühgeburt or premature birth, compared with the time other females in the animal kingdom are pregnant with their young.

On the isle of Sicily, Prince Salina, also the ‘leopard’, is living the end of his life, fully conscious of, as well as resigned to the fact that his world, the world of his aristocratic colleagues, is slipping away fast, escaping them. However, the cool head of any prince must never get overheated; self-discipline affords the aristocrat a body that will not over-exert itself; if so, this would immediately become visible in pearls of sweat on the brow. A few drops – á la…; gushing with sweat: never! Not being obliged to ever function in one way or another, certainly not to work ‘in the sweat of thy face’, princes would become almost inhuman. An aristocrat strides, always moving with majestic gestures. Wenders has doubtlessly learned from Visconti, that grandmaster of the cinematographic chess-game, making all those delicate moves with his images. In order to express the tardy decay of time, the Italian cineaste is not so much making use of symbols, as using the images themselves.

Il Gattopardo, lasting more than two hours, retards, slackens and decelerates time; especially so, in its glorious last half hour. The climax is enacted by Prince Salina, performed by Burt Lancaster in what must have been the role of his life. During a luxurious and luxurious party in one of the neighbouring palaces, the older man suddenly feels a twitch of the heart, then looks in a mirror to observe sweat on his brow. He withdraws into one of the side rooms. Once again, looking at himself in the next mirror, he looks at the sweat running along the temples and over his cheek, mixing with what suddenly turn out to be tears of agony; sad to be getting old, also ashamed of losing his poise. Finally becoming human, he draws his handkerchief and swipes the fluids away.

Prince Salina has achieved the moment, both in his own life and in the history of Sicily, when he cannot actually move any longer without the risk of moving too much. In the slow tempo of the drops of sweat leaking on his face, we recognize the decay of the feudal order to which he still belongs. Visconti also used this same image in his screening of Thomas Mann’s Death in Venice. Like the ageing Prince Salina, the protagonist, a composer and a prince of the arts, who is acted by Dirk Bogarde, has been moving in his hotel and walking through town, overly calmly so. Nonetheless, in a deck chair, on the hot beach of the Lido, he will die, with sweat streaming over his face. Who knows – from old age, from the raging cholera, or perhaps from Sehnsucht for the angelic Russian boy, also residing at the Lido hotel, with whom he has fallen in love.

That wistful longing for the adolescent boy had been the reason for postponing his flight by train from the disease-stricken city; a cholera epidemic, from which he otherwise might have escaped. Not only is the sweat gushing on his countenance, it also makes the cheap hair-paint run which a barber has used to try and make the composer look a decade younger; to be able to, at least, seduce the boy into a smile. As with Prince Salina’s sweat and tears, this aesthetic disaster of a little back stream on the temples is a preview of the lifeless, lonesome body of the man, dead and crumpled in his beach chair.

While looking at a restored copy of Il Gattopardo, in what for a Northerner seemed to be a Saharan summer in Amsterdam, an oppressive heat was scourging the town. The cinema had become a hothouse. Amongst the crackling sounds of dry Sicily on the screen, I could almost hear the small brooklets of sweat streaming over my body; perhaps, many such rivulets turning into a little river flowing down the tilted floor of the old cinema Rialto. In that dark room, I became very conscious of the fact that I may not be an aristocrat, but that I certainly am an intellectual who was prepared to suffer his own sweat ad maiorem gloriam pulchritudinis – in praise of beauty.

When leaving the movie theatre, I was shocked to hear one petty-bourgeois girl telling another petty-bourgeois girl, that she considered it ‘not a bad movie at all’, from which to her taste the last half hour ‘might have been cut out…’ That half hour is the half hour of the film; a half hour, without which the movie could not have been what it is: an ode to slow time. Ai, those youngsters; sic transit gloria mundi; the End of Time is near. To compensate for the vulgarity of my sweating, I strode down the somewhat cooler, tree-covered streets of Amsterdam.

3 Walking History

During our long walks in the Wörlitzer gardens, my colleague John broached a subject of conversation which had engaged me already since long; the issue of what might be the historically different tempi of man moving about. The theme hit me the day when an adolescent, like Heidegger’s man ‘being thrown into the world’, within the span of twelve hours I had found myself transported from quiet Amsterdam into the whirlpool of London City. Out there, for a long time, I felt radically lost; like Edgar Poe’s infamous protagonist, drawn into the vortex. To put it mildly: I thought that all Brits had gone crazy; running around like fools, for someone equipped with the normal instruments of seeing hardly to be perceived in their hasty movements. To be honest, I must admit that the same English roadrunners also stopped in their tracks, the moment I asked them for directions as to where to go. In Paris, by contrast, the town in which I had the same experience of tempo change, people just ran through me whenever I tried to ask them the way.

Being gripped by the issue of time-perspective, I dedicated many years of my life to writing on tempo-constraints put on industrial labour. My PhD took one of its mottos from Friedrich Nietzsche, who wrote about Americans and ‘their breathless haste while working; here, they even think with a stopwatch in their hand…’ Perhaps, one might also do research on the history of the historically diverse tempi of walking, and on the way various kinds of clothing and shoes have influenced this; from wooden shoes to plateau shoes; from crinoline to pencil skirt; from sport shoes to pumps; from a coat of mail to the postmodern pit-bull smoking. In a shop in Dessau, with the Wörlitzer gardens we would be walking, I discovered a little book with designs by the painter Blechen. On one of them, a drawing from 1892, we observe the Villa D’Este near Rome. Between two lanes of mighty trees, one sees a couple walking; the woman, in one of those long, wide skirts which obviously forces her, thus her mate, into an aristocratic gait.

By the way, when did that silly rage of the popular medical gallop, also called jogging, come into fashion? Most probably, it needed a civilisation in which the better sport’s shoe had already been invented; footwear, with special soles and supple leather, or even made of newly-invented synthetic materials; as well as the support of a marketing culture of grand allure, and of course, the permanent research to invent ever better shoes. To write a walking-history, books on etiquette might be of help, to check whether there have been prescribed paces of walking for various classes and sexes. The reader is reminded of the prevention of sweat on aristocratic faces.

Empirical knowledge of what is self-evident, will always remain a wafer-thin affair; an historian will find it difficult to find material to document people’s common everyday-life habits and manners. It is said that contemporaries of the philosopher Immanuel Kant could set their watches on the regularity with which he passed the bridge in the town of Köningsberg; he was always walking the same route, always in precisely the same amount of time. However, even at the time the question remained if this was an especially Kantian tempo; or, more generally, the manner in which intellectuals then used to move; or, if his pace was what he considered the ideal pace of the whole of mankind, setting an example; after all, morals were a subject dear to Kant’s philosophical humanism.

An observation by Jules Barbey D’Aurevilly is to the point. In his fine essay on dandyism, he concluded that even if Herculaneum might have been uncovered and laid bare, again rid of its lava dust, its excavation would prove nonetheless, that only one catastrophe may be enough to cover a whole civilisation with its dust, thus to eliminate a society and its culture, to be lost to us forever; perhaps, also covered by the lid of historical lava, which deprives us of the visibility of its original state. ‘The history of our manners is composed of mere memory; memories are never more than approximations.’ Here, we are reminded of Christopher Hampton’s fine book on the Etruscans, of whose cultural achievements, except for a few tombs, nothing is left. We know nothing of their music and their literature; nor of the manner with which they walked. Discussing the various tempi of the human gait must necessarily remain guesswork.

D’Aurevilly, who was writing in 1844, likened the aristocrat to that supreme prototypical dandy ‘Beau’ Brummell, who ‘was able to introduce an antique kind of calm into our modern agitation; this, with the help of affectation and an ineffable grace of a polished ease of manner; if not with abandon, as well as with a certain dry sense of humour.’ Together with the society which gave birth to it, Dandyism would finally fade; like the feudal world of Prince Salina’s Sicily had been fading, after the unification of Italy had begun. Whether a true aristocrat, or someone merely affecting royal airs like ‘Beau’, it had become clear that this nil mirari, this gently and calmly walking on clouds like true gods, wondering at nothing, had had its own historical niche.

Whereas D’Aurevilly was the conscious and keen chronicler of Brummell’s aristocratic dandyism in practice, he also foresaw its end. By contrast, Balzac was more of a petty-bourgeois who gave Brummell’s dandyism its theory, thus making of Brummell a prophet post hoc. In a little treatise titled Théorie de la démarche, written in 1833, Balzac phrased a set of axiomata with which he wanted to keep alive what Brummell’s admirer D’Aurevilly had already condemned to Marx’s ‘dung heap of history.’ According to Balzac ‘the self-conscious slow pace announces a man, who owns time, free time; a man, who is rich, noble, wise and full of thoughts.’ Someone following this code, could always become a dandy – whenever and wherever. In Balzac’s mind there was no consciousness of historical ‘progress’, and no acceptance of the fate of all history – to become… history. He suffered from anachronism.

4 Walking In Difference

.

Walking indifferently, strolling aimlessly – yet, not being indifferent. Of a sudden, the eye falls on something, not seen before; it becomes the focus of attention. Walking in difference. The paradox of sauntering.

Cultural differences in walking? Surely. Having spent most of my life in Haarlem, a provincial capital situated close to the Dutch capital of Amsterdam; having lived a year near New York City, more specifically Manhattan; as well as, during my sabbatical, half a year of survival in the city of Rome with a month-long heatwave – one has lived the differences.

At certain hours, walking in Manhattan is an endeavour to avoid, dodging the risk of being bowled over by other pedestrians. Especially at the beginning of my stay, I felt forced to participate in a rat race; the tempo of moving over the pavement was obnoxious, only violently interrupted when crossing a street, when everybody would be abruptly forced to make a stop and wait, en masse, for a pedestrian’s red light. Then, like the starter’s gun in an athletics race, green would be on, the permission to race on.

For the visitor, that is for someone not wilfully partaking in this melee of fast-moving atoms, rather someone still out to have ‘an experience’, Manhattan will add another disappointment. Apart from the height of all the sky scrapers which at the end of a day have given you quite literally a pain in the neck, there is indeed nothing to be really experienced. Manhattan is a desert of extreme impulses, however devoid of anything ‘special’; it is empty of details, which are always the things to be actually observed. This lack of details may add to the hectic speed of all those going about their business; if they did not already have to race, what reason in their surroundings would there be to take it easy?

Seated inside a cab, one is still noticing nothing. All this running around is a very limited activity, most people take a cab. Their number in Manhattan indicates one of the main causes of American obesitas: one may have been running around for a while, but one does not run enough. Once at home, Americans tend to sit in front of the telly where there is also nothing to be seen. When the alarm bells about obesitas began ringing, diagnosed as death-cause no. 1, the American cure became, once again, another kind of racing called jogging. Racing against fat, running against fate; racing against one’s Self, yet again with an indifferent gaze. For the aesthete, the visual effect was disastrous; with people suffering from bodypositivity flopping their fat thighs against one another, or people without the slightest athletic finesse plodding along. When – finally – ‘the weekend’ has arrived in Manhattan, the pace drops quite unexpectedly. If not playing some sport, people in Central Park are now suddenly sauntering; or they stroll along streets to get a bagel. This relaxation has something of a pose: ‘Look at me, relaxing…!’ The weekend gaze has now also become ‘relaxed’, noticing nothing in specific. It tells you: ‘Cool, man – I am cool!’ Yet, the jogging also goes on.

Walking provincial Haarlem is a different ball game. I commenced to do this rather late in life, due to the fact that in the past every single day I had been either teaching at the university in faraway Delft, or studying and writing at home. Each walk in my hometown now became a kind of voyage of discovery, gently floating through, in and out of not yet revealed small alleys; almost every single building is ‘special’, architecturally, historically or otherwise. Instead of speeding you up, the town is slowing down the walker; he becomes a stroller. The same, notably, in nearby Amsterdam.

On my holidays, walking all those smaller European towns, everybody also had seemed to be strolling; as if they were going nowhere, even if they were going somewhere. They were walking the streets like they stroll the parks or their own garden. It reminds one of Goethe who, in his Elective Affinities, wrote about der Takt des Schrittes – the gentle rhythm of sauntering through the garden. The German writer may have written rather bad poetry; in his novels he was a master of metaphors. Takt is a musical term, referring to the floating rhythm of a composition played well, a tune on which people are swinging their dance.

In the garden, this ambling, if not meandering pace allows both Goethe’s lovers to converse, as well as their eyes to take in the splendour of the variety of flowers all around them, and the building-up of a sky-scape high above. At low speed, all and everything may be singled out as foreground against the background of everything else; changing perspective one is.

Strangely enough, in a near past even pedestrians in the gorgeous metropolises of Europe – Amsterdam, Rome or Paris – were also just walking, as if they took their time to enjoy the walk, before they would reach a goal. Instead of the indifferent gaze of the Manhattonian, the Continental stroller’s eye becomes attentive, remarking houses, flowers, other people. In his study of the passages, the covered shopping streets of Paris, Walter Benjamin found this attitude in extremis in the flaneur Baudelaire, who wrote: ‘The perfect flâneur – that impassioned observer, and his immense pleasure to find his home in the shade, in the meanders of what is volatile, in all that moves, in what is transitory, infinite. To be outside himself, yet to feel at ease wherever he is.’

The ideal of today’s everyday walker in Rome or Amsterdam is not that of the flâneur any longer; postmodernity has hit this world, cruelly so… Haste has become the code. Yet, compared with the American towns, there still seems to be something of the inquisitive person present, excited by the not-yet-seen, someone with a calm, yet attentive eagerness.

5 The Metre of Pacing

The stride betrays whether someone is

already walking his path: look at me,

how I go! Whoever is approaching his

goal, is dancing.

Nietzsche, Also sprach Zarathustra, IV

The German writer Goethe was a marginal man, hovering between the desire to be an aristocrat and his actually being a bourgeois, if not a mere servant. In his novel Die Wahlverwandtschaften or ‘elective affinities’, a book on the dialectics of the sexes, the writer seems to have been contemplating the same issue of slow walking. He considered the obstacles that might interrupt what he called someone’s Takt des Schrittes during a garden walk; the metre of a slow, seigneurial stride, like dancing. However, in contrast with Balzac’s timeless appeal to the garden lover, Goethe – like D’Aurevilly – seemed to be well aware of the fact that the fluent, unforced bearing of the garden walker was doomed to disappear; it belonged to an age in decline. We are speaking of an existential revolution; it seems that this aristocratic tact of a gracious walker’s pace could not be saved by simply taking away the barriers mentioned by Goethe; of necessity, the coming of modern society was producing these very same obstacles.

According to Goethe, each decade knows ‘its own kind of happiness’; a statement, reminding one of Herder, who already somewhat before him had taught the same point; each culture will reach its very own apex of bliss. Relevant is to discover that both the Frenchman Balzac and the German Goethe express their intense dislike of the hurried pace of industrialised man, an idea which would find an echo in Nietzsche’s quote on the United States with its stopwatch world. And, sure enough, the time would come when, with the greatest distaste, I would observe in Dutch Elswout’s Paradise children run around; undisciplined by their parents, playing soccer on meadows where first delicate spring flowers were budding; scaring away birds, whose delicate songs were seducing the ear; kids, wholly unaware of the intentions of the creators of these gardens.

Obviously then, that same age of the older Goethe and the younger Balzac saw the decline of the aristocracy as a historical category, its social class coming to its end; if not also the end of the reign of the petty-bourgeois upstart, disguised as a would-be nobleman. Perhaps, the critical philosopher Adorno was right, when he wrote that the walking pace of the liberal bourgeois had been less constrained, more relaxed than the former sublime stride of the aristocrat. However, like Nietzsche, he also saw this world of the liberal bourgeoisie vanishing as fast as it had come up; its would-be liberal rule over society to be replaced by an industrialised, authoritarian order in which the commands of money and efficiency would determine the hurried tempo of everyday life, finally leading to marches of fascism. From then on, any post hoc affectated aristocratic dandyism could not be but forced; a fake shadow of the sublime Brummell, whose intent to mimic the aristocrat had still been of an honest intent.

From the beginning of the 20th century, the still relaxed bourgeois pace of the end of the 19th century would become deceitful and anachronistic; a show of hypocrisy. Both the would-be dandy and the relaxed bourgeois would in fact be negating the real, harsh order of the new society, thus being reduced to sheer ideological affectation. Nobody will escape the age he is living in, even though one may agree with Richard Wagner’s modernist observation that ‘precisely the Zeitgemässe quality of a work of art, fitting into its time, has something questionable.’ We may, perhaps, try and escape the prison of the age we live in; try and walk the Great Gardens as Goethe would have it; with a dance-like metre of our gait. As we may suffer the ridicule of others.

6 Godspeed

The true lover of novels and philosophy needs to be able to adapt his reading to the intrinsic tardiness of the German poet Jean-Paul; to be impatient in the task of savouring literature, makes one fail to understand a text. To read true literature and true philosophy is to walk its text at a proper pace. The hasty student of Adorno’s masterpiece Minima Moralia, will surely bang his head into the sometimes-self-conscious and intended incomprehensibility of the language. It was Adorno’s firm conviction that the style of a proper critique of capitalist society would have to be equal to the complexity of its subject of criticism; in his case, the complex, contradictory world of late capitalism. One must write in a ‘difficult manner’; writing too ‘easily’ about it, would make that society seem less complex than in fact it is, thus failing the aim of criticism. Then again, conquering the difficulty of such texts, while struggling to understand them and taking all the time they need to be read properly, may afford one the immense satisfaction of achievement.

Pensive reading, pensive walking. Perhaps, a bit like the flâneur as described by Baudelaire who, around 1840, strode the shopping malls of Paris, those famous passages, accompanied by a tortoise on a leash; walking with the pace he had prescribed to his readers. Irony may be of help.

Schiller wrote that he would not have liked to live in another century than the one he had been born in; he was perhaps a wise man. It was a century, also an era which was coming to an end. However, taking my meditations on the tempi of walking seriously, now having turned the corner of the twenty-first century, it may very well be a privilege of the more liberal, as well of those who are as handicapped in body and spirit as my colleague John and me, to act as if we were aristocrats. Perhaps, hindered by our defects, as yet to stride sublimely through all the magnificent gardens with all those follies beckoning us to stand still, and to meditate on the shortness of life, as well as on the spuriousness of our mere temporary Paradisiacal state.

This noble tempo of the aristocratic gait is also reserved for Germany’s white Hefe Weizen beer, which is beyond praise; a liquid, drawn off so slowly, that it demands a noble self-discipline when you feel the pressing urge to quench your thirst; as we did wait patiently for its arrival, after our long, hot and slow walking through the Wörlitzer gardens. Surely, such beer must be of blue blood. One should also be reminded of the fact that nobility is not hereditary; not something genetic, but a socio-historical attainment.

Once upon a time, Northern Europe called an acre a ‘morning’ or morgen, the surface that a man, sound of limb, was supposed to be able to plough before noon. Nobody in his right mind would have demanded from that farmer to do his labour in the slow stride of the nobleman or, for that matter, without the use of his horse whip. Thus, historical differences between social classes arise; true aristocrats strode, without leaving a material trace in the dust they walked on. At the time, though, the true nature of such noble men might be traced in the impressions they left in the tenuous floor of our mind; as did so many great aristocratic philosophers who enlightened us or, for that matter, those princes who created their grand gardens with their intriguing follies.

The pace of lords; the pace of the Lord, even though I know all too well that He will never move – if Aristotle is right; He is always throning, that is – if the Bible is right. I am also quite conscious of what is said about Him; that He is supposed to be all-wise, all-word, all-seeing, all-knowing. ‘Rest’, thus Balzac’s third axiom, ‘is the body being silent.’ Each time, I put my worn 33 rpm LP with Mozart’s Requiem on the music-player, I am eagerly waiting for his Rex tremendae majestatis, with that eerie salva me. Thou Prince, of an awesome majesty…; how stupid I am: in all His awesome, unmoving majesty and being all-powerful, he must of course also and always be moving; that is, on the heavenly music of Mozart’s mass of sadness, the voices keeping the tempo of his stride, the basso continuo speeding his pace one tempo up. The great myth of all aristocrats has been that they originate from the gods.

7 Garden Melancholy

This anachronistic experience of Mozart’s music is even intensified, when it concerns disciplined nature; gardens, parks, all of them laid out beautifully, often kept in pristine condition. In the lush environment of the Wörlitzer gardens in Germany’s Anhalt-Dessau, it came as quite a shock to observe a young plantation of lined-up trees in a barren field. Suddenly, I became conscious of the fact that visitors preceding me, those who came here two centuries before me, also those who planted the first generation of trees, had all witnessed something quite different from what I was seeing during my visit. The fine oaks are now, unmistakably, more than two hundred years old. A decade after in 1765 they were planted, when ‘the father-gardener’ Prince France was walking the park, they were only tiny trees. We are enjoying his visionary design; his gardeners died, long before they could even check whether their design answered to what had been envisioned.

Worse, worse that is for them, one may seriously doubt whether they ever enjoyed their own gardens. The small fry of those young trees, even saplings, did not allow for what was intended as the garden’s true joy. When rounding the bend of a serpentine path, the attraction of each English Garden involves the experience of a sudden perspective on a surprising folly; up till that moment, it had been hidden by full-grown trees and luxuriant shrubs. During the first decade, these follies must have been immediately visible already from afar, giving themselves away before the fact of even being a folly; thus, betraying the intentions of their makers. The trees were yet too minuscule. Larger shrubs might have helped; however, these also take a lot of time to fully grow. Lucky for him, since the first plantation Prince Franz lived for quite a while; his gardeners, though, had died much earlier.

Franz had another good reason to be sad; his still-born daughter, in whose memory he erected the most beautiful folly in his Wörlitzer park: the Golden Urn, created in 1769, the same year when one began to lay out the gardens.

.

.

Now hidden, at the centre of three different perspectives, it must then have been visible from anywhere; there would not have been a tree or a shrub around to hide it from view, which is of the essence for the slow English Garden walker who wants to be surprised, thus heightening the melancholic aspect. One ought to be literally stopped in one’s stride and be awed; this was for later years.

8 An Invalid’s Pace

Even today, during a little evening walk along the river Elbe’s beautiful outer flatlands with their gracious clumps of trees, I feel that I cannot but observe them through the frame that is housing the best of Caspar Friedrich’s sometimes crude paintings: Das Grosse Gehege bei Dresden, painted in 1832. It suddenly becomes too complex and so confusing.

.

.

Memories gather in the mind, the moment when I also remember the manner in which my colleague and I had been walking the landscape gardens of Elswout, Wörlitz, Stowe, Ermenonville and many others. We had read all these wise men on the way to walk a garden, supposedly with an aristocratic stride and with a noble calm and a sweatless countenance. A few years before the two of us began our travels, John had an operation on a brain tumour, an intervention which left him handicapped on one side. The man walked in a rather curious manner – if walking is the word; always balancing on his one proper leg; like an unsteady archer, more or less aiming the other one, hoping it would land on a safe spot of terra firma. Before we had begun our travels, he had already managed to acquire a certain acrobatic savoir, suffused with clownesque irony. Both these achievements were indeed necessary.

If the two of us had to climb a hill, all went well; more or less so. Going down, however, the trained mechanism of controlling that damned second leg began to fail him; like a happily married couple, arm in arm, we would descend a knoll. Added to the pleasures of such cumbersome walking was my inflamed Achilles tendon; not serious in comparison with John’s catastrophic affliction, yet nasty enough. When on these garden visits there were other visitors about, they would inspect the two of us with curious, if not deprecating looks, transformed as we had been into another garden attraction; a mobile folly…

That year in Weimar, there was this unbearable summer’s heat; being two Dutchmen, we considered it tropical. In the middle of a Germany that had been united only very recently, our pedestrian handicaps combined with this oppressive warmth, forcing our tempo to an almost aristocratic stride. Not my will, thine be done… On my own, without my crippled friend at my side, I might have looked more like Gramsci’s casually dressed ‘organic intellectual of the working class’, at least capable of some tempo. Now, however, we spent those two long, long days in Paradise, perhaps experiencing it as its creator must have done; Prince Franz, who might have wanted us to enjoy it a little more comfortably, though. It was clear, that a metamorphosis of two Dutch professors into two sweatless German little princes was out of the question. As John was walking faster than he normally would, the exercise was immense; it also made him look even funnier than he normally looked. I was forced to stride through these gardens at what might best be considered a museum pace which, as we know all too well, is rather fatiguing. Sweating we were; looking very much like two steaming workhorses from the farm, more so than two gentlemen riding them. Thanks to all this pomp and circumstance, we looked much older than we actually were, which was a good thing. Gardens are meant for old folks, whatever the wishful-thinking Belgian garden freak, Prince De Ligne, had assumed about young ones mating on his lawns, their children later to play on them.

As with all else in this cosmos, it remains a matter of relative tempi and of time perspective. When he was only thirty-three years old, the age of the Lord, Prince Franz had already built his folly of the Gothic House. When, in the eyes of later centuries, he did not as yet have that much of a past, he would often retire there. However, to be thirty-three in the 18th century would have made Franz comparatively as old as we were with our fifty-five years at the turn of the 20th century. Now, lazily walking the gardens was transforming what, at first glance, seemed to be an ultimate form of anachronism into a delightful, if not sublime synchrony. Each moment, while rounding the serpentine paths of Wörlitz, curves rather suiting our joint funny walk, we were expecting Prince Franz to appear around the next bend, graciously walking towards us with a warm welcome.

9 Devilspeed

In my hometown, Montmorillon in France, a man was pointed out to me; in his past he has been an architect, so I was told. He has a heart defect. In order to stay alive, his doctor must have instructed him to walk so many paces a day. From time to time, I observe him moving past my house; in his case, ‘moving’ seems to be semantically more correct than ‘walking.’ As if the devil is after him, he is progressing fast, with too small steps, so as to make as many of them as possible per minute. When he is passing, one imagines his pedometer clicking, slicing up times in ever smaller bits, making the small stint of live left to him all the more obvious.

He won’t outrun his fate. What is worse: his face is lacking the lustre and the laughter Nietzsche advises a man to present to his fellow men, showing that he is strong enough to face the inevitable. Instead, this man seems to be joylessly suffering the verdict of doctors who are trying to save his life by condemning him to look like a clown; sad-faced, the fear of death is written all over it, fitted with a red nose running from the cold. According to that German philosopher, one should be looking the world straight in the face, confronting its misery and enduring it with a salvo of laughter.

This man must be unaware of the wisdom contained in P. N. van Eyck’s verse, in which Death is awaiting whom he wants to meet, when and wherever he has decided to meet him. After the gardener’s demise, Death is answering his former master – posthumously so:

Smiling, he answered: “No threat it was,

for which your gardener fled from here.

I was surprised, when in the early morning

I found him here at work,

the man I had to reap that evening in far Ispahan.”

.

Sierksma, 2024 Haarlem/Montmorillon